What I learned from Valentin Tomberg about meditation

Some reflections after reading Meditations on the Tarot: A Journey Into Christian Hermeticism

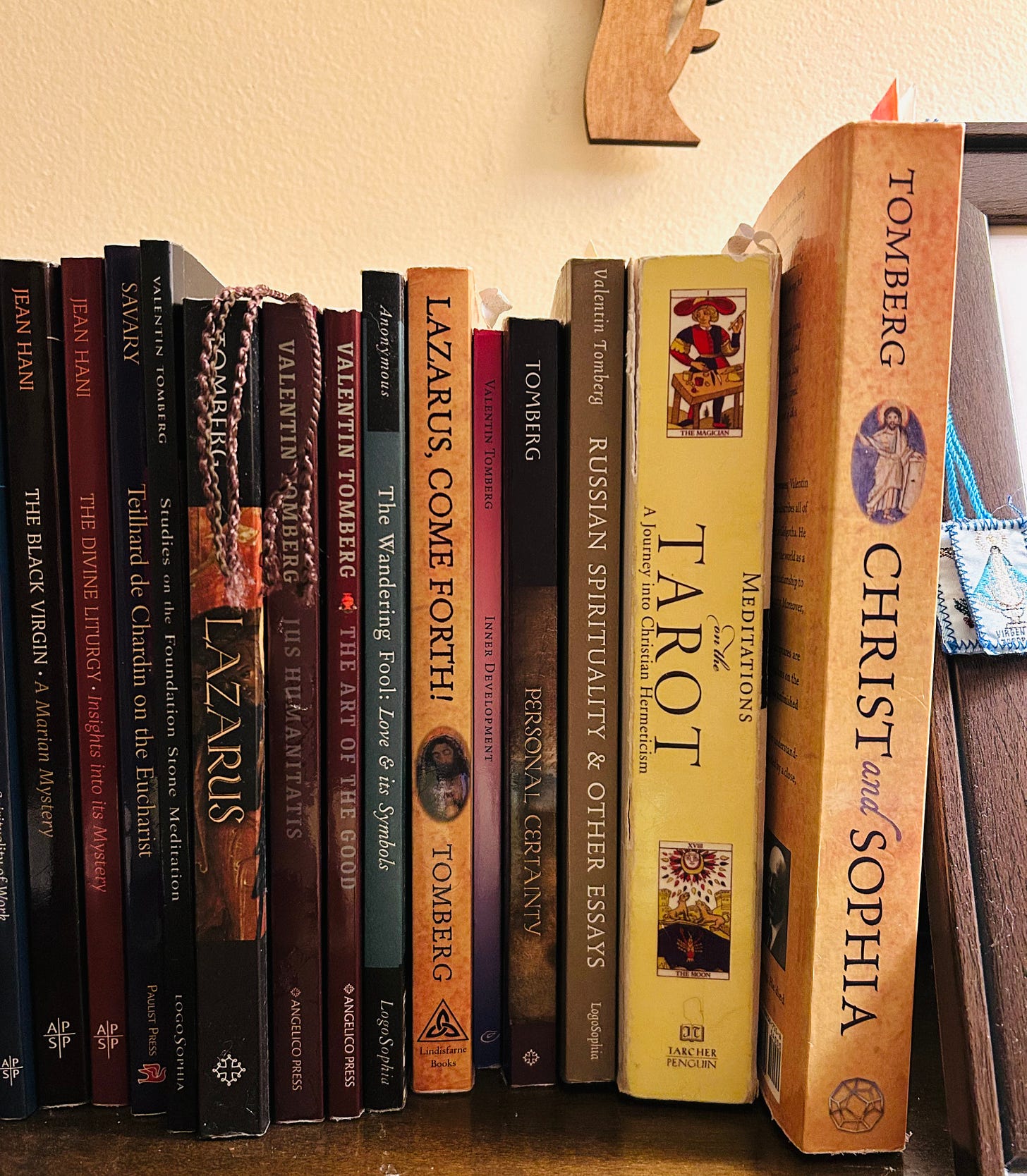

In the days leading up to the new year, I found myself reflecting on my journey with Christian esotericist Valentin Tomberg, who I encountered three years ago when I read his anonymously published Meditations on the Tarot: A Journey into Christian Hermeticism. Since that time, I’ve gone on to read his other translated works and undertake an esoteric meditation course on the Lord’s Prayer that he offered in the early 1940s. This work has been among the most transformative, and intellectually and spiritually stimulating experiences of my life.

It’s thanks to Tomberg that I’ve been able to develop and maintain a consistent meditation practice for over two years. In this reflection, I’d like to share a bit of what I’ve learned from him about meditation, also known as spiritual exercises.

The Value of Meditation

Americans often overlook the rich meditative traditions within the West and turn toward Buddhism or other spiritual systems originating in Asia and other parts of the world. Mindfulness meditation is particularly popular in the U.S., but I was never that drawn to it. Several years ago, I attempted discursive meditation, where one meditates on spiritual or philosophical themes, but had to pause due to various life circumstances. I returned to it after reading Meditations on the Tarot and entering a season in my life that demanded self-discipline, endurance, and daily spiritual nourishment.

I realized in reading Meditations on the Tarot that it was both a guide to meditation and the result of decades of meditative and contemplative practice. Tomberg was not only an adept at meditation, but he was also a religious mystic, occultist, and intellectual, deftly weaving together capacities within consciousness that most people would prefer remain separated. (In occult terms, Tomberg had gone a long way in developing his mental body, which is distinct from the physical, etheric, and astral planes.) The purposes of meditation, according to Tomberg, are to transform the soul faculties of thinking, feeling, and willing, to attain depth of insight, and to collaborate with the spirit realm, thus participating in cosmogenesis. Spiritual exercises help us awaken to the essential concerns of human life and our responsibilities in addressing them.

The dominant culture and religious outlook within America tends to prioritize propositional knowledge and be wary of altered states or mystical experiences accessed through sustained practice (áskēsis). In an unfinished manuscript on the topic of gnosis, Tomberg contrasts typical philosophical aims in the West with the practice of Buddhism and Indian Yoga:

“Philosophers (at least in the West) come to a halt once they have arrived at a conceptually clear, logically or experientially well-grounded and clearly-defined view. Their concern as philosophers is thereby at an end: as far as they are concerned, they have clearly and convincingly accounted for how matters stand and why they cannot be otherwise. For practitioners of Yoga, however, this end-result of philosophical thinking only marks the beginning of what they are concerned with. For them, this result of philosophical observation signifies an opening to immerse themselves in it: to think, will, breath, and live themselves further into the object until they are completely awakened to it.”1

A consistent meditation practice can lead to Christian gnosis, which Tomberg defined as deeper insight into the mystery of love. I have adopted Tomberg’s definition of gnosis, a word that is historically associated with dualistic metaphysical philosophies and viewed suspiciously by orthodox Christians. However, Tomberg distinguished between false gnosis and true gnosis:

“Heresies result from a lack of insight into the mysteries of love. Arid, formalistic theological systems are intellectual commentaries on the original – commentaries that attempt to translate a gnosis alien to them into their own intellectual language. This can and may happen; it is indeed the proper task of theology as a science. But it may only happen when the original is itself understood not intellectually but gnostically. There must be a living gnosis standing behind the theology.”2

For Tomberg, Christian Hermeticism is one means of attaining personal certainty (gnosis) that is awakened through engagement with symbolism and undergirded by formal religious and scientific traditions. This offers a greater degree of freedom in one’s spiritual life and creative endeavors while ensuring one responsibly contributes to the further development of the broader culture one inhabits.

Now, many people who pick up Meditations on the Tarot are initially overwhelmed by the density of thought contained in it. An article Tomberg wrote during his Anthroposophical years3 provides a hint of why this is so. In it, he weaves together a triad of differing approaches to meditation – one idealistic and ascetic in nature, a second prioritizing methods and processes, and a third focused on results. This latter pragmatic approach, Tomberg says, tends to be attractive to Western Europeans and Americans, but can devolve into a mechanical exercise that projects the goal of meditation down to the material plane.

“This hindrance can be eliminated by taking up, before and alongside the meditative work, a comprehensive cognitive effort to penetrate the concepts communicated by spiritual science,” wrote Tomberg. “Through this effort, thinking is released from its materialistic tendency. It is gradually trained to think of spiritual and intimate things in a spiritual and intimate manner. Thus it becomes capable of envisioning the results of meditation in advance in such a way that instead of arousing desire, it brings forth sacrifice and renunciation in the soul.”4

I’ve found that Meditations on the Tarot encompasses these various aims of spiritual exercises and more. Those who read closely will discover the highest of ideals, methods for embodying them, and criteria for assessing their fruitfulness. Michael Frensch, one of the book’s translators, wrote that Meditations on the Tarot requires a “tremendous effort to think,” but eventually leads to one becoming an active co-thinker with Tomberg and experiencing a moral warmth centered in the heart.

“The reader has then really walked an inner path,” Frensch wrote. “He has experienced something of what the author describes as ‘hermetic initiation’ as an inner intimate reality in his passage through all 22 letters; his capacity for knowledge, indeed his whole being, has been transformed.”5

There’s a lot more that could be written about this topic as well as other things I’ve learned from Tomberg, but I will leave it here for now.

Happy New Year.

This passage can be found in Personal Certainty: On the Way, the Truth, and the Life, published in 2023 by Angelico Press.

Also from Personal Certainty.

It’s important to note that Tomberg’s spiritual views evolved over his lifetime. I chose to engage his published writings in good faith and with discernment, and have found valuable insights and guidance in all of them.

This passage can be found in Russian Spirituality and Other Essays: Mysteries of Our Time Seen Through the Eyes of a Russian Esotericist, published in 2010 by LogoSophia.

From the ebook version of Frensch’s A Friend From Beyond the Grave: My Encounter With Valentin Tomberg, published by Novalis.

I took a two year study group on MotT with Karen Rivers. Each participant took a different chapter to present, and she filled in whatever wasn't understood or needed fleshing out. I'm probably going to start my own group, as enough people have asked me to do so. Tomberg has been transformative.

Tomberg changed my life. I have read Mott three times and, additionally, another two times aloud. I am glad you wrote. Good job. Alchemical-weddings is very connected here as well. Have a look. Write more, too.